Rida Hirani: When Zebrafish Teaches You Patience

Dissecting Danio rerio

The small needle was hovering over the clear zebrafish embryo. My hands were shaking. If I don't do this right, all these embryos could die... and everything I had worked on would be ruined. I watched videos, practiced with colored dye, and gone over each step, but the hardest part was putting what I had learned into practice. At that moment, I understood that research wasn't just about being smart; it was also about being patient, careful, and mentally ready.

During my third-year independent research at Lander University, I investigated the BLK gene, a member of the Src Family Kinases—proteins that regulate cell growth and signaling but may lead to cancer if dysregulated. I chose zebrafish embryos because they are transparent, which lets me see early embryonic development up close. My goal was straightforward: silence the BLK gene and see how it affected the embryos’ body plans. The execution, I soon learned, was anything but straightforward.

The first real problem I had was with microinjections. It takes a lot of skill to get a gene silencer into a one-cell embryo. If you go too shallow, it won't reach the embryo; if you go too deep, it could burst. My first attempts with dye went into the sac surrounding the embryo instead of the embryo itself. Moving on to the actual gene silencer, which is invisible to the eye, I couldn’t tell if it worked. The first set of injection results was exactly the same as those of the control group, which was a silent reminder that I still had a lot to learn.

I felt a mix of embarrassment and frustration. I had a lot of questions, like, was the liquid media the right temperature? Was my hand pressure stressing the embryos? But I did not feel comfortable asking my professor directly. Instead, I turned to a friend and peer in the lab. When I shared my worries, she laughed and said her own first injections had been a disaster too. We laughed so hard for a few minutes that I almost forgot why I was worried. Then she suddenly got serious and said, “Okay, enough joking, here’s what actually worked for me.” She showed me her needle angle adjustment technique, and seeing it in action finally clicked. I went back to my own injections with renewed confidence, and gradually, the embryos began to respond the way I had hoped. When I saw my first successful results, I felt relieved and excited. I had finally turned hours of practice into something useful.

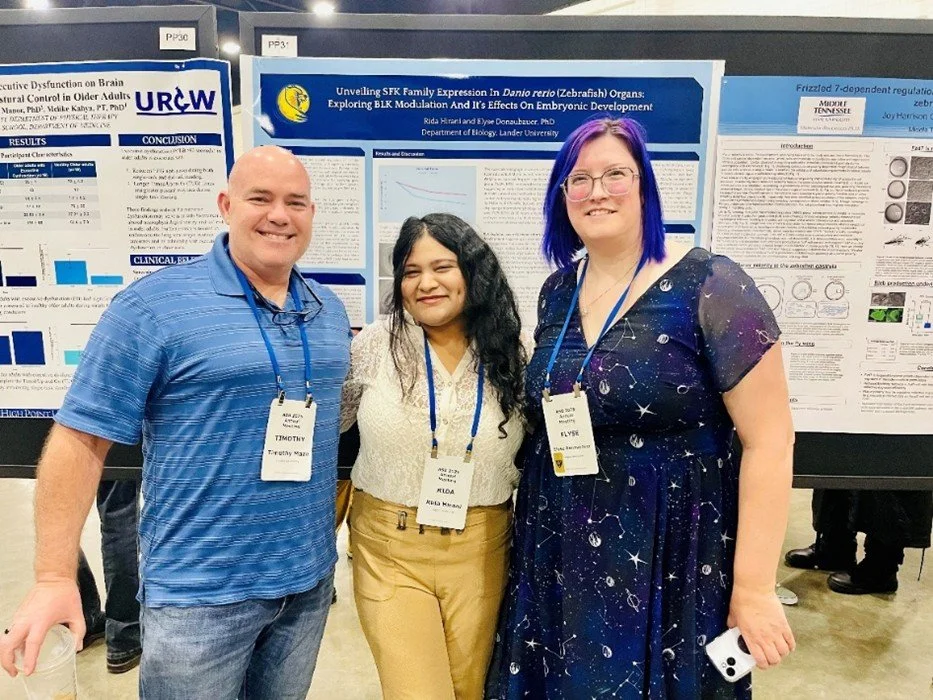

Presenting Research at Association of Southeastern Biologists (ASB) Conference 2025

When I presented my work at the Association of Southeastern Biologists (ASB) Conference, it became even clearer that hard work pays off. It was exciting to see my data on display, talk to other researchers about my findings, and answer questions about my project. That moment, when I connected semesters of hard work to the curiosity and insight of others, made all the effort worth it. I was proud, excited, and more positive than ever that I was on the right path.

One of the simplest but most impactful qualities I acquired was learning to accept failures. I had been too focused on getting perfect results and did not realize how interesting it was to learn from the process. Taking responsibility for my mistakes and repeating experiments made me more confident and better at making scientific decisions. Through this experience, I also learned that research turns complex science into practical solutions.

The BLK project was not only about discovering a gene but also about learning how to deal with challenges, think critically about what went wrong, and celebrate progress. Every failure became a lesson, and every success a reminder that hard work and determination pay off. Achieving perfect data does not always fulfill the goal; one must engage with the process, learn from errors, and reflect deeply.

Beyond lab skills like microinjections, RNA extraction, and zebrafish dissections, this research has helped me build qualities that matter in medicine: patience, attention to detail, resilience, and reflective thinking. In the lab, precision is equally as critical as patient safety in a hospital setting. Being persistent in fixing failed trials implies being persistent in resolving clinical issues. As I was injecting every embryo with extreme care, it reminded me of how small procedures or actions could have a loud impact on the whole outcome, which applies to patient care as well.

Rida Hirani, from Greenwood, South Carolina, is expected to graduate in Spring 2026 with a Bachelor of Science in Medical Biology. She is preparing to apply to medical school and hopes to become a physician, with a particular interest in the field of cardiology. Passionate about heart health, Rida is committed to advancing her knowledge and skills to provide high-quality care to patients.